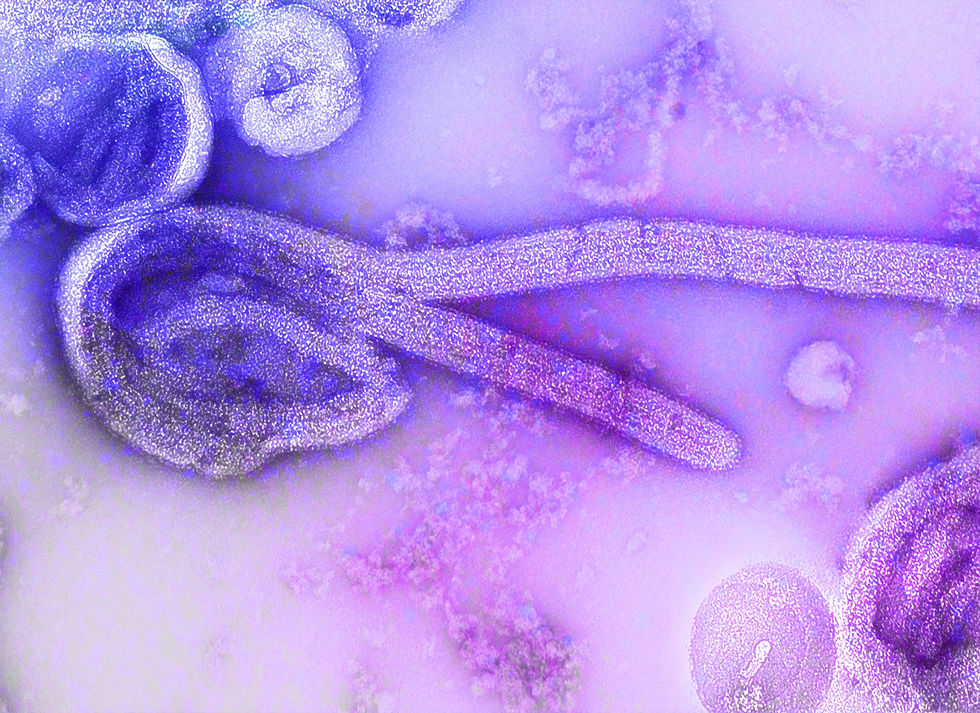

Ebola in the Congo: An unprecedented public health crisis

- Lawrence White

- Sep 1, 2019

- 3 min read

In July, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared that the Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is a public health emergency and warrants a larger response from the international community. This outbreak is proving to be a major challenge for aid organisations, as many areas of the DRC are ravaged by violence which prevents aid workers from moving freely around the country. Despite healthcare workers now having experimental drugs that can drastically increase survival rates from Ebola, the violence and lack of infrastructure means that it is incredibly difficult to treat every person who may have been infected with the virus. As a consequence, this outbreak is proving exceptionally dangerous for not only the DRC but also the wider region of Central Africa. At the time of writing, it has already left almost 2,000 people dead and a high probability that the virus will spread further and possibly into large urban areas. To combat the spread of the virus, more resources need to be urgently made available to the international aid agencies working on the ground in Central Africa to ensure that people are being treated as rapidly as possible.

The complexity of this outbreak cannot be understated. According to the Human Rights Watch, the eastern provinces of North and South Kivu are home to 140 active armed groups. In 2018 alone, violence in these provinces left 883 people dead and 1,400 more were abducted. For controlling a healthcare emergency, the situation is nightmarish. Not only is it dangerous to reach communities where an outbreak occurs, but there is now an increased risk that Ebola clinics will be directly attacked. In February, two Ebola clinics in North Kivu were attacked by arsonists, resulting in the destruction of crucial lifesaving equipment. This is symptomatic of a climate of increased suspicion surrounding the international aid agencies. Since locals haven’t been immediately seeking treatment at the clinics, they have often only been admitted once there is little chance of recovery. This has created a chilling feedback loop where locals become wary of the clinics, as their friends and relatives have often never returned from them, leading to rumours spreading like wildfire.

With this in mind, it becomes easy to see why aid workers are struggling to stop the virus spreading. For it to be effectively contained, people need to access Ebola treatment centres at the first sign of infection, which due to the nature of the virus is not always clear. In addition, people who may have been in contact with the virus also need to be quarantined for 21 days to minimise the risk to their communities. With limited resources and a deteriorating security situation, it is incredible that the WHO and other aid organisations have actually managed to do so much. They have so far successfully vaccinated over 170,000 people and monitor a further 20,000 people daily for signs of the virus.

Despite their best efforts, the aid agencies have not actually brought the outbreak under control and a much larger international response is needed to fully contain it. The declaration of a public health emergency has undoubtedly helped to mobilise more resources, with the UK alone pledging an additional $63 million towards containment efforts. However, there remains a large funding gap, which the WHO is urging donor countries to urgently fill. For the outbreak between 2013 and 2016, over $2 billion was needed to control and end the spread of the virus. In the case of the DRC outbreak, a lack of preventative funding now could lead to the virus spreading regionally and ultimately result in a similar multibillion dollar response being required at a later date. With such a predictable outcome, it is shocking that aid agencies are not being given the funds they need to deal with the second worst Ebola outbreak in history.

Of course, even if the current outbreak is brought under control, the lack of basic healthcare throughout most of the eastern provinces of the DRC means that infections could re-emerge in the years to come. In fact, this current Ebola outbreak is the 10th to wreak havoc in the country over the last 40 years. Realistically, the actions of the aid agencies are just a drop in the ocean compared to the longstanding healthcare improvements that the country desperately needs. But with large parts of the country being an active conflict zone and a half-hearted international response, it’s possible that the DRC could continue to be home to the Ebola virus for many years to come.

Image - Unsplash.

Comments